When Did Christianity Begin?

(← click) How did Christianity start and spread? Many in the West, especially in the United States, believe that Christianity went into a dormant state with the death of the 12 Apostles or when it became allied with the state in 325 A.D. under Constantine the Great, Emperor of the Greco-Roman Empire, and only with Gutenberg's invention of the printing press in the 15th century and the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century did Christianity arouse itself from its slumber. But that is a vast oversimplification of Church history.

(← click) How did Christianity start and spread? Many in the West, especially in the United States, believe that Christianity went into a dormant state with the death of the 12 Apostles or when it became allied with the state in 325 A.D. under Constantine the Great, Emperor of the Greco-Roman Empire, and only with Gutenberg's invention of the printing press in the 15th century and the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century did Christianity arouse itself from its slumber. But that is a vast oversimplification of Church history.

For the first 2 or 3 centuries, what we now call Christianity was then considered first as a branch of Judaism like the Essenes or Zealots, then as a spin-off sect of Judaism that most Jews had rejected. And yet, this new belief in Yeshua as the Messiah not only of the Jews but also of all nations persisted and expanded, even under severe persecution by the pagan state and society, as the fulfillment of God's promise to Abraham that in him all nations of the earth would be blessed (Gen. 12).

It was only after 325 A.D. when this new "fulfilled Judaism" was tolerated by society and the state, that followers of "the Messiah" in Aramaic, or "the Khristos" in Greek (both titles mean "the Annointed One") began to assemble the various writings of the Apostles and other early believers, then decide which writings taught the true faith and which were doubtful or even fake, "pseudo-"gospels and letters. Early in his life as a churchman, St. Athanasius of Alexandria defended the true faith against the heresy of Arianism at the First Ecumenical Council at Nicea in 325 and then compiled the list of 27 gospels and letters that 50 years later was officially accepted as the New Testament canon.

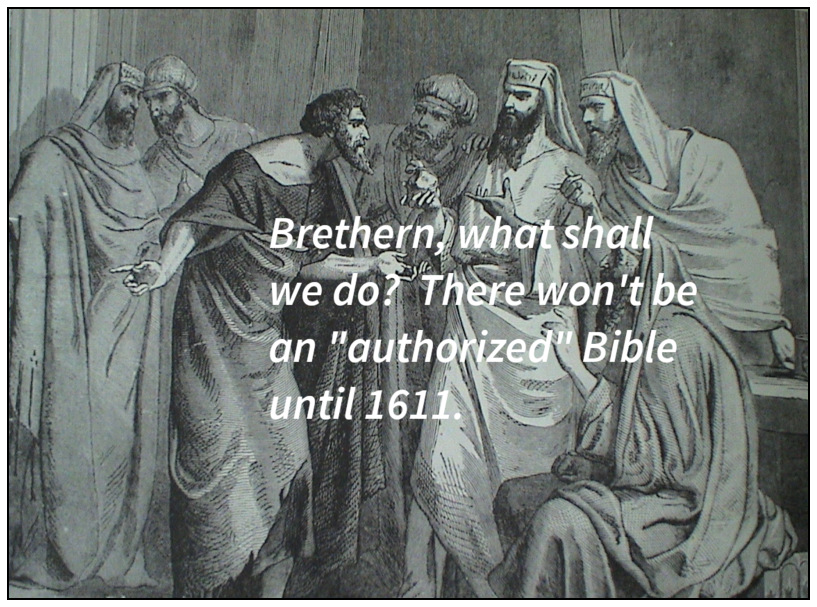

So for about 360 years, this new faith was mainly spread orally by its evangelists and Apostolic bishops ("missionaries" is the English meaning of "Apostles"). The bishops meeting together in councils decided what was the correct interpretation of these Scriptures – holy writings – and how to orally teach the people, because copying these writings by hand was very tedious, time-consuming, and expensive. Only with the invention of the printing press in the 16th century did it become possible for the average believer to possess a copy of the Scriptures.

By Luther's time a century later, people had become accustomed to think that having a Bible was the way things always were, just as today's teenagers think that there have always been smartphones and people have always been able to communicate electronically over the Internet. They have never experienced life in any other way. This is called "anachronistic" thinking. An "anachronism" is projecting today's culture and its technology back into the past when they didn't exist.

An example of this in churches is to see icons or stained glass windows of the 12 Apostles each holding the Bible as a bound book... but the "codex" – the bound book with pages and covers – hadn't been invented until the 6th century. Up until then, hand-written or "manu-script" copies of the Scriptures consisted of several scrolls of parchment – specially-cured animal skins. The four Gospels would be hand-copied on one scroll, several Apostolic letters hand-copied on another scroll, etc., just like in the Jewish synagogues.

An example of this in churches is to see icons or stained glass windows of the 12 Apostles each holding the Bible as a bound book... but the "codex" – the bound book with pages and covers – hadn't been invented until the 6th century. Up until then, hand-written or "manu-script" copies of the Scriptures consisted of several scrolls of parchment – specially-cured animal skins. The four Gospels would be hand-copied on one scroll, several Apostolic letters hand-copied on another scroll, etc., just like in the Jewish synagogues.

Thus, as the our quote above "Brethern [sic], what shall we do? There won't be an 'authorized' Bible until 1611" illustrates, it's a big mistake to assume that the Bible we have today could have possibly been the sole authority for faith and practice. For 1500 years, very few people had ever seen a Bible or the scrolls that it consisted of. Much was handed down orally: "And there are also many othr things which Jesus did, which if they were written in detail, I suppose that even the world itself would not contain the books which were written" (John 20:21 NASB).

So the only things they could rely on often were icons depicting Bible scenes and oral tradition – the correct interpretation of the Scriptures by Apostolic bishops and the priests under their authority: "So then, brethren, stand firm and hold to the traditions which you were taught, whether by word of mouth or by letter from us" (2 Thes. 2:15 NASB).

As St. Peter wrote – "Knowing this first, that no prophecy [telling forth] of the Scripture is of any private interpretation. For the prophecy [telling forth] came not in old time by the will of man: but holy men of God spoke as they were moved by the Holy Ghost" (2 Peter 1:20-21 KJV). The connecting word "For" indicates there is a logical connection between the inspiration of the "holy men of God" who wrote the Scriptues and holy men of God – the Church Fathers – who interpret the Scriptures, not private intertpretation by any "common plowboy or milkmaid" – as one of the Protestant Reformers once said.

St. Athanasius of Alexandria wrote the manuscript essay "On the Incarnation of the Word" on a scroll in the early 300s A.D. That's why in our printed version there are no page numbers, only chapter numbers and paragraph numbers! We'll be teaching this online course right up to "the Incarnation" – Christmas – starting on Nov. 28 and ending on Dec. 23. So click on the above "On the Incarnation" photo to get all the links to this essay as a printed booklet, an e-book, and this course! See you there on Nov. 28!

Go to ARC-News to read our free e-newsletters and Subscribe!